Did you know there is a simple calculation you can do to see how much money you will need to live well in retirement?

It’s based on a number you will already know – the amount you currently earn every year.

Using that, you can work out the annual amount to aim for to replace your income and meet your needs comfortably when you retire.

The best bit is that this number will be personal to you and will reflect your own lifestyle.

Here, we explain how to work out your own retirement income target – and then how to do a vital second reality check to ensure it will be enough.

Your own number will also reflect whether you are single and therefore shouldering higher household costs, or in a couple and sharing costs, and also whether you rent or are a homeowner.

You might need to rethink your income goal if it seems too modest after those factors are taken into consideration.

Once you have your personal retirement income target worked out, you can check just how close your pension savings are to achieving it – and what to do if you’re falling short.

Your retirement calculation

The idea is to use your current income as a starting point and adapt it for how your lifestyle may change in retirement.

You will need something near to your current income, minus work-related costs such as travel, clothes, lunches and sundries including coffees on the way to the station, plus new spending on hobbies, socialising and holidays during your extra, post-work free time.

The figure you arrive at is called your ‘target replacement rate’ benchmark, according to the investment platform Hargreaves Lansdown, which used figures from the think tank Resolution Foundation to come up with a simple method to get you to an approximate ‘target’.

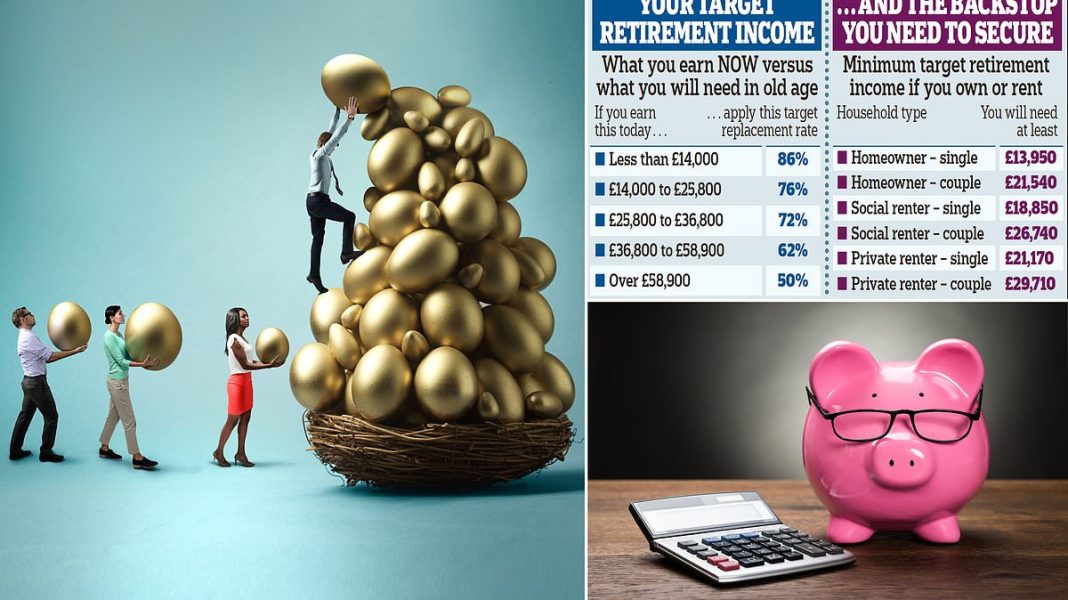

Here’s how it works. Take a look at the table on the next page to see which income category you fall into, then apply the percentage in the right-hand column to your own annual earnings.

For example, say you are on £30,000 a year before tax. Your replacement rate is 72 per cent, so your pensions and other assets would need to generate you an income of £21,600 a year in retirement.

What if you are on £45,000 a year? Your replacement rate falls to 62 per cent, so the income you are aiming for is £27,900.

If you aspire to a better lifestyle in older age than the one you enjoy currently, you will have to bump up your replacement figure – and if you think you’ll be happier with less you can dial it down.

Then there is a second calculation you must carry out to check you are on track for at least a minimum retirement lifestyle.

This measure, which is known as the Living Pension and is published by the Living Wage Foundation, should be treated as a backstop to ensure that you will have enough to cover your basic everyday needs.

To work out your Living Pension requirement, check the table on the following page. Your number depends on whether you will be living in a single, dual (or more) income household in retirement, and whether you own your home.

For example, if you are a single homeowner, you will need a minimum income of £13,950, whereas if you are in a couple you will need a minimum of £21,540 combined.

However, the Living Pension’s rental costs don’t factor in housing benefit and other subsidies for lower-income households.

If you are eligible for these, it will help your budget in retirement. More and more younger people are likely to still rent in retirement and may need a higher minimum income when they stop work.

A homeowner in retirement needs at least £13,950, according to the Living Pension requirement, whereas a private renter needs £21,170 – £7,220 a year extra.

If you qualify for a full state pension – currently worth £12,000 a year – and you are saving into a work pension under automatic enrolment, you should meet the Living Pension minimum target.

What’s good about this calculation

Figures published last month put a pounds and pence figure on what is needed for a minimum, moderate or comfortable retirement lifestyle.

These numbers are published every year by the industry body, the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA).

The most recent suggested a couple needed £21,600 for a minimum lifestyle, £43,900 for a moderate one and £60,600 for a comfortable one. While these provide a useful rule of thumb, critics point out that they do not reflect personal circumstances.

For example, Jason Hollands, managing director of the wealth-management firm Evelyn Partners, says that even if you achieve an income of £60,600 in retirement, that may not feel comfortable to you if that is just a fraction of what you enjoyed during your working life.

He adds: ‘While the PLSA have had a stab at coming out with estimates of how much income is required for a “moderate” and “comfortable” retirement, in reality there is a huge amount of subjectivity about what constitutes “comfortable” or financially “secure”.’

But these calculations from Hargreaves Lansdown, published in a new Pension Adequacy report and carried out in partnership with the forecasting firm Oxford Economics, aim to remove some of the subjectivity by coming up with a number that reflects your own circumstances.

Helen Morrissey, head of retirement analysis at Hargreaves Lansdown, says that unless workers have a reasonable idea of what they will need in retirement, they will remain in the dark about how much they have to save.

‘Without it, we risk groups of people continuing to under-save and receiving a nasty shock when they retire,’ she adds.

‘Others could strive to hit a target that’s far too high, causing themselves unnecessary financial stress and potentially turning them off pension saving altogether.’

Under the Hargreaves Lansdown calculations, lower earners are far more likely to meet their target retirement income than the PLSA guidelines suggest.

This is because your definition of what a moderate lifestyle looks like may well be a smaller figure if you’re already living on a low income while also working.

But conversely, higher earners are likely to find it harder to hit their target replacement income than to hit the PLSA definition of a moderate or comfortable retirement.

That is because one person earning £100,000, for example, would need a target replacement income of £50,000 in retirement, which is considerably higher than the £43,900 needed for a comfortable retirement under the PLSA definitions.

How close are you to saving enough?

To work out whether you are on track, you will need to investigate your existing pensions and consider your other assets.

For each pension you have, find out:

1. Whether it is a final-salary or defined-contribution scheme.

Defined-contribution pensions take contributions from both the employer and employee and invest them to provide a pot of money on retirement.

Unless you work in the public sector, they have now mostly replaced more generous gold-plated defined-benefit pensions or career-average pensions, which provide a guaranteed income after retirement until you die.

Defined-contribution pensions are stingier, and it is savers who bear the investment risk of the pot not growing quickly enough, not their employers.

2. Its current value.

For a defined-contribution scheme, this should be a simple pounds and pence figure.

For a final-salary scheme, your provider should be able to tell you the guaranteed income it is likely to produce and pay out after your retirement according to its rules.

3. What you are likely to have by retirement age.

You can use our pension calculator to see whether you will have enough. Then, you need to think about how you will turn your work pensions into an income.

You typically have the option of taking up to one quarter of your money as tax-free cash, and using the remainder to secure an income for the rest of your life.

If you have defined-contribution pensions, you will need to use them to generate your own retirement income.

This means looking at buying an annuity – a product that provides a guaranteed income – or staying invested via an income-drawdown plan and taking money from your pension as you need it.

Alternatively you can use a combination of an annuity and a drawdown plan.

At current rates, a 65-year-old with a £100,000 pension pot could buy an annuity that pays out £7,933 for life, or £5,884 and rising by 3 per cent every year to counter the effects of inflation.

If the same 65-year-old decided to use drawdown, they could draw the same income without running out of cash until they reached the age of 82, assuming investment growth of 5 per cent.

Salary-related defined-benefit pensions pay out an income according to the terms of the individual scheme.

4. Look at the value of your other assets.

Don’t stop there. Check your Isas, any investments you hold outside them, buy-to-let property and so on.

Estimate what income they could generate to top up your pensions in retirement.

5. Check your state pension.

Add the income figures above to what you anticipate getting from your state pension, which is currently £230.25 a week or around £12,000 a year if you qualify for the full new rate. Get a state pension forecast at gov.uk/check-state-pension.

Pension savings shortfall fix

Matched contributions: Extra top-ups to your pension are frequently available, particularly from large employers.

For example, an employer might already automatically match 3 per cent of your earnings as its minimum contribution to your pension.

But it might be willing to make 4 per cent, 5 per cent or 6 per cent in matching contributions if you opt to save a higher proportion of your income.

Personal contributions: There is a relatively generous annual ceiling on how much you can pay into your pension and get tax relief – the equivalent of your annual salary, up to a maximum of £60,000 for most workers.

You might want to consider a one-off top-up to your pension if you get a pay rise or a bonus, or as an alternative to sticking spare cash in your Isa.

But if you have not already maxed out matched contributions, make a permanent ongoing increase if you can afford it.

Salary sacrifice: Arrangements like this are a nice little earner for many workers and their employers. They are essentially a legal way to dodge National Insurance payments.

Employers allow staff to take a supposed ‘pay cut’, but the money gets ploughed into their pension or put towards some other benefit such as childcare or an electric vehicle instead, and both sides pay less NI as a result.

Merging pensions: Savers tend to collect a string of pension pots during their working lives, and schemes make it fairly easy to roll them up if you choose, though there can be drawbacks.

A tidying-up exercise can reduce fees and paperwork and bring new investment options but you can lose valuable benefits, so investigate before you take the leap.

Missing pensions: If you’ve lost track of old pots, try the Government’s free Pension Tracing Service at gov.uk/find-pension-contact-details – but take care, as many companies using similar names will pop up in the results.

These will also offer to look for your pension, but try to charge or flog you other services, and could be fraudulent.